Ah, Vermont—the land of bucolic hills, quaint dairy farms, and... smuggling? Yes, beneath its picturesque charm, the Green Mountain state boasts a centuries-old legacy of profitable defiance. From the Embargo Act of 1807 to the rollicking days of Prohibition, Vermont has always shown a flair for bending the rules, especially when it came to liquor.

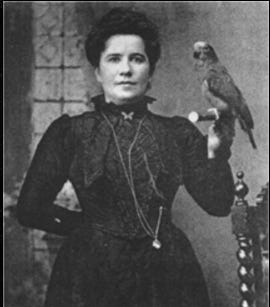

This entry in the New England Prohibition Road Trip centers on Vermont’s scenic rebellion. Serving as our window into Vermont’s complicated history with Prohibition is Lillian Miner Shipley Fleury, better known as Queen Lil. Her Palace of Sin—a “line house” on the Vermont-Quebec border that was part speakeasy/part bordello—was as much a statement about Vermont’s experience with Prohibition as it was an unparalleled business venture.

For Lil, who combined the spirit of a Silicon Velley startup founder with the cunning of 1920s crime boss, breaking societal norms (and the law) was a lifelong pursuit. Vermont may have tried to erect barriers to vice, but Queen Lil fashioned them into steppingstones for her own lucrative ventures.

Land of Loopholes

To understand Vermont’s complicated relationship with Prohibition, we have to travel back an additional century. In 1807, Thomas Jefferson persuaded Congress to pass the Embargo Act, with the goal of cutting off trade with Britain and France and stifling their economies. Instead, Vermont’s economy tanked. Did Vermonters give up? Hardly. They smuggled goods across the border, became privateers, and (in the ultimate act of sass) sold supplies to British soldiers during the War of 1812. By the time Prohibition rolled around, skirting the law was practically a state pastime.

Speaking of bans on alcohol, Vermonters officially spurned hard liquor before Andrew John Volstead drew his first breath. Inspired by Maine’s groundbreaking 1851 liquor ban, Vermont hopped on the temperance wagon in 1853, when it prohibited the production, sale, and consumption of alcohol. But true to form, Vermonters quickly decided that what’s good in theory doesn’t always work in practice. Smuggling flourished, secret stills bubbled to life, and the statewide law was more of a suggestion than a mandate. Throwing up their hands, the state legislature adopted a “local option” law in 1902, allowing towns to decide for themselves whether to prevent the sale of liquor. Although most towns remained officially “dry” up to the Volstead Act, hard liquor was never more than a train ride away.

From Small-Town Rebel to Big-City Ambition, and Back

Enter Lillian Miner. Born in Richford in 1863 (or in 1866), she was an unlikely candidate for infamy. Her early life was quintessentially Vermont—one of 11 siblings growing up in a rural town in the Northeast Kingdom. She hightailed it out in the only way available to most young women of her time, by getting married. At the age of 16, she hitched her fortune to Charles “Albert” Shipley, a ne’er-do-well so poorly thought of that the Richford Gazette mocked his death, proclaiming that the chickens could now sleep in peace. During their marriage, Lillian and “Ol’ Ship” travelled the land, selling snake oil medicine among with other marginal pursuits, according to local lore, with occasional stints in Boston, where Ol’ Ship came from. Their only child was stillborn, and Ol’ Ship died soon after, in 1896.

For the first time in her life, Lillian was on her own.

She remained in Boston, in the vibrant West End, a neighborhood teeming with immigrants and low-income families struggling to make their way.

At the turn of the 20th century, Lillian identified herself as a “waitress” and a “lodging housekeeper” to the local authorities, although rumor had it her establishment at 373 Columbus Avenue offered carnal comforts in addition to room and board. When Boston authorities began to sniff around too closely, Lil beat a hasty retreat back to Vermont, looking for new opportunities in her old stomping grounds.

The Palace of Sin: Where Borders and Boundaries Blurred

Ever the forward thinker, Lil identified a Plan B for herself even before she left Boston. In 1911, she paid $500 for a parcel of land just over the Canadian border, where a hotel had burned to the ground. What a sweet deal that purchase proved to be. After some initial litigation with the US and Canadian (structures were not allowed to span two countries), she was able to build a “line house.” The three-story building dubbed the Palace of Sin defied borders by standing half in East Richford, Vermont, half in Glen Sutton, Quebec. By 1913, the Palace of Sin had already earned a reputation for its card games, alcohol, ladies of the night, and high jinks.

When national Prohibition arrived in 1920, business boomed for Queen Lil. Her one-stop shop provided music, dancing, and (most importantly) a steady flow of Canadian booze. The Palace’s location almost flush with the Canadian Pacific Railway ensured a reliable clientele of thirsty customers from Boston—as well as smugglers, locals, and thrill-seekers who appreciated its proximity to the legal gray areas of the international border.

Lil’s true genius lay in her ability to straddle more than just borders. When US authorities stopped by, she had the booze moved over to the Canadian side, and vice versa. It was the ultimate “catch me if you can” scenario, and Queen Lil played it masterfully.

A Woman Ahead of Her Time

Running an international business during Prohibition was no small feat, especially for a woman. Queen Lil not only survived but thrived in a man’s world, leveraging bluster, wit, and a good dose of financial grease to keep the Palace of Sin open for business. The state’s half-hearted efforts to enforce Prohibition meant that Lil’s operation became a hub for the booming underground economy.

Queen Lil experienced one notable run-in with the law, in 1925, when she was not given her usual heads-up about an impending raid. The raid was a joint US-Canadian effort, a necessity since the front door to the Palace of Sin was on the Quebec side. According to the June 12, 1925, account in the Richford Gazette (“Notorious Line House Raided”):

“Five couples were found in bed; three on the American side and two on the Canadian side; two men and two women were absolutely nude and the others scantily clad. The three couples found on the American side were arrested and a quantity of beer seized.”

Vermonters monitored the subsequent legal proceedings with bated breath, no doubt expecting a dramatic reckoning, with prison time meted out (finally!) for Lil as a punishment for the “licentiousness” of her business. Instead, the result was a fine of $150—for “keeping a disorderly house.” If anything, the trial solidified Queen Lil’s reputation as a woman who could outwit the system.

Home Is Where the Hustle Began

Queen Lil added a new chapter to her story with her marriage to Levi Fleury, a widower with a houseful of children. True to form, Lil didn’t allow her second marriage to relegate her to the background. Even as she embraced married life a second time around, she maintained her title as “head of household” on official records while she ran her establishment—a fitting nod to the iron will and entrepreneurial spirit that drove her success.

When the Palace of Sin faded away in the late 1920s, Lil and Levi pivoted to a new enterprise: farming. The pair acquired several local properties, swapping bootleggers and card games for livestock and harvests.

It wasn’t exactly the stuff of that drives the sale of scandal sheets, but it’s telling that after all the graft, booze, and seamy scenarios, Lil found peace in the rhythm of rural life, working the same rocky soil that she had first called home. The Queen of Contraband passed away in 1951.

A Legacy as Old as Vermont Itself

Queen Lil’s life wasn’t just about breaking the rules—it was about writing her own. Whether as a madame, a businesswoman, or a farmer, she carved out a place for herself in a world that rarely made room for women with bold ideas and bigger ambitions. Her legacy is the reassuring message that reinvention is the ultimate rebellion.

Queen Lil was far from the first Vermonter to find profit in defiance, and she won’t be the last. From Jefferson’s embargo to the Prohibition smuggling routes over land and water, Vermont has long served as a crossroads of creativity and contraband. Lil may have trafficked in vice, but she also embodied the entrepreneurial spirit that defines the Green Mountain state—a place where the quiet beauty of the landscape belies the boldness of its people.

Places to go

If you’re interested in visiting Queen Lil’s old stomping grounds, there is plenty of low-key fun to do. You can visit the historic East Richford-Sutton border crossing, once one of the busiest between the two nations (and very pretty). Folks in town still remember the bridge that spanned the Missisquoi River, which was destroyed by the Flood of 1927, considered the worst natural disaster in the state’s history.

Throw caution to the wind and take a drive down the East Richford Slide Road, which sends you, without a passport, into Canada before looping back into Vermont. Some claim that there is a mysterious gravity hill along the Slide Road, enabling cars to move uphill.

It’s a half-hour drive from Richford to St. Alban’s, where Queen Lil died in 1951. St. Alban’s was a dastardly liquor distribution center during Prohibition thanks to its prime location on the northern end of Lake Champlain. The US Customs Service set up its Lake Champlain Boat Patrol here in 1924, to curb the movement of hard liquor that was transported via “Champlain Rum Boats.”

Further to the southwest, stop in at Burlington, the largest of Vermont’s 10 cities. Nestled right on Lake Champlain, Burlington has a couple of centuries of experience with smuggling. The Lake Champlain Maritime Museum does a great job illustrating the history of life along the Lake, including during Prohibition.

Though every Vermont ski resort has at least one decent run named for bootlegging, you can’t beat Smugglers’ Notch for the authentic feel in the peaks of illegal back country liquor transport. Alcohol has travelled over the steep hills since before Route 108 was laid down. The skiing is good, and the view unmatched.

Places to Eat and Drink

For a combination of “best view” of Lake Champlain and “best food,” you can’t beat the Inn at Shelburne Farms, which offers seasonal farm-to-table dining, just a short drive south of Burlington. From the terrace, you can spend time imagining all the Rum Boats plying the waters at midnight. Although Shelburne Farms is now a nonprofit organization and well worth a visit in its own right, during Prohibition, it was a private residence owned by Lila Webb, the youngest daughter of William Vanderbilt.

The Prohibition Pig in Waterbury is a fine stop for BBQ and suds after a day spent skiing. You can enjoy your meal with your dog if you dine in the patio at the Back Bar.

Further south, near the ski country of Bromley and Stratton, you can dine at Johnny Seesaw’s Restaurant, in a building constructed from the reclaimed remains of a 1930s dancehall and speakeasy.

Sources and Further Reading

Krakowski, A. (2016). Vermont Prohibition: Teetotalers, Bootleggers, & Corruption. Charleston, SC: The History Press.

Okrent, D. (2011). Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. New York: Scribner.

Prohibition in the Champlain Valley – Lake Champlain Maritime Museum

Prohibition, 1920 — Vermont Historical Society. Some interesting oral histories of people who witnessed bootlegging.

Wheeler, Scott (2002). Rumrunners and Revenuers: Prohibition in Vermont. Shelburne, VT: New England Press.