Welcome to the New England Prohibition Road Trip!

Prepare to delve into the rum-running days of the 1920s, uncovering the hidden stories of a dry era that defied its own rules.

As the author of a historic mystery series set in 1919 amidst the charming Berkshire hills, I’m inviting you on a journey through New England’s roaring Prohibition era—exploring the blind pigs, shadowy characters, and schemes that kept the region’s shot glasses far from empty. Together, we’ll pull back the layers of intrigue and contradiction behind a nation that outlawed the bottle but couldn’t resist the drink.

Our first stop is Boston’s North End—where greed and ambition collided in one of the country’s most surreal industrial accidents. In 1919, just past noon on an unusually warm January day, a molasses tank towering over this densely populated neighborhood ruptured, unleashing a wave of molasses that killed 21 people, injured scores more, and wrecked entire city blocks.

North End, circa 1919. Map courtesy of Wikimedia.

The timing was uncanny—the tank burst one day before Congress approved the Volstead Act and a year before Prohibition took effect. Although the tragedy’s immediate cause was the buildup of fermenting fumes, the actual culprit was a distilling company’s Prohibition-fueled greed.

Molasses: The Syrupy Engine of Pre-Prohibition Industry

In the years before the 18th Amendment silenced America’s saloons, molasses was the life of the party. This dark, sticky by-product of sugar cane didn’t just sweeten Boston’s iconic baked beans—it supported the nation’s war efforts and stocked bar shelves. During World War I, molasses served as a critical source of ethanol, the volatile backbone of munitions.

The Purity Distilling Company, a subsidiary of the U.S. Industrial Alcohol Company (USIA), was not about to miss this boat. In 1915, the company hastily built a massive steel holding tank on Boston’s waterfront to cash in on the rising demand for industrial alcohol. The North End location was convenient in terms of unloading the product from the ships plying Boston Harbor, but a questionable decision in terms of public safety. Ninety feet in diameter and fifty feet tall, the tank held 2.3 million gallons of molasses. Well… most of it, anyway. From Day 1, the tank groaned when it was filled with the viscous substance. It leaked, as well, to the immense pleasure of neighborhood children, who would gleefully scoop up free molasses from the base and seams.

From Day 1, the tank groaned when it was filled with the sticky substance.

Despite countless warnings from workers about the structure’s inadequate construction, USIA did nothing to reinforce the tank. The company’s “safety” concerns centered on the anarchists in town that were rumored to be scouting for ways to disrupt the supply chain for the Great War. USIA did not hesitate to post armed police officers around the clock at the Commercial Street site but dismissed any talk about leaks and straining seams. In fact, the company painted the gray tank brown, to make the molasses stains less noticeable.

By January 13, 1919, the tank had been filled and refilled a total of twenty-nine times, but today’s load from the Millerio—the one that led to the explosion—marked only the fourth time the tank had been filled to its capacity.

The Explosion

January 15, 1919, was unseasonably warm—the thermometer edged past 40 degrees Fahrenheit after a bitter cold spell. The sudden thaw likely sped up fermentation inside the filled tank, creating pressure too immense for the brittle steel to contain. At 12:40 PM, with a sound like gunfire, rivets popped, and the tank ruptured. As the New York Times described in a contemporary account,

A dull, muffled roar gave but an instant’s warning before the top of the tank was blown into the air. The circular wall broke into two great segments of sheet iron which were pulled in opposite directions… The greatest mortality apparently occurred in one of the city buildings, where a score of municipal employees were eating their lunch. The building was demolished and the wreckage was hurled fifty yards.

A 25-foot-high wave of thick molasses surged through the North End at 35 miles per hour, ripping buildings from their foundations, drowning horses, and claiming lives. The disaster’s shocking scale captured headlines around the world, detailing the immense human suffering, the heroic rescue efforts of Red Cross workers and cadets from the U.S.S. Nantucket, and the monumental challenge of cleaning up the residue.

A twisted elevated train structure damaged in the Molasses Disaster. Photo courtesy of Boston Public Library’s Molasses Disaster Flickr Collection.

Almost immediately, a troubling question also emerged from the chaos: how could such a catastrophic failure have happened?

How could such a catastrophic failure have happened?

Inevitably, scrutiny turned to the actions of the Purity Distilling Company and its parent, USIA. The injured survivors and grieving families of those who lost loved ones filed 119 cases against USIA, which were consolidated into a single lawsuit overseen by the Massachusetts Superior Court-appointed auditor, Hugh W. Ogden.

Hugh W. Ogden circa 1920. Photo Courtesy of the University of Pennsylvania Archives

Over the course of a grueling five-year investigation, USIA advanced a defense blaming anarchists who planted bombs to sabotage the tank—a claim that, given the paranoia of the First Red Scare, was not immediately dismissed. The proceedings involved over 1,500 hundred pieces of evidence and the testimony of more than 1,000 witnesses.

The prolonged trial allowed a cold light to shine on the negligence surrounding the tank’s construction. At the heart of the story stood one man whose decisions paved the way to catastrophe: Arthur Jell.

A Human Face to Corporate Negligence

Arthur Jell, USIA’s treasurer and ill-prepared overseer of the tank’s construction, personified the haste and hubris that doomed the tank’s construction. Born in Ontario, Canada in 1878 and a veteran of the Boer War, Jell immigrated to the United States in 1909. A public accountant by trade, he climbed the corporate ladder with an ambition as towering as the ill-fated tank itself. Promoted from USIA’s secretary to its treasurer in 1914, he was being pushed to finish the high-risk construction project as quickly as possible. The Great War would not last forever, nor would its profits.

Jell is shown seated in the first row, second from the left. Photo courtesy of the Government of Canada’s archives.

Jell’s testimony during the investigation revealed a staggering mix of ineptitude and indifference. He admitted that he had bypassed essential safety protocols, failing to submit any construction plans to an architect or engineer, consult trained professionals, or seek the advice of a metallurgist regarding the suitability of the steel used. Most damning was Jell’s decision to forego a full water test to verify the tank’s structural integrity. Investigators at the time surmised that the steel used in the tank’s construction was 10 percent thinner than specified in the design—a more recent analysis indicated the flaw was far worse than originally suspected.

Adding to the scandal were the wrenching accounts from workers who had repeatedly warned Jell about the tank’s defects—only to be summarily dismissed. These revelations pointed to flaws not only in the tank’s construction, but also to USIA’s systemic weaknesses as a company where no one was equipped to assess the tank’s shortcomings or address their implications. As a result, an unstable behemoth was allowed to brood in one of the most congested neighborhoods in Boston—an area far removed from the comfortable communities where USIA’s executives lived.

In April of 1925, Hugh W. Ogden found that USIA alone bore responsibility for the tragedy. Although the financial restitution Ogden initially identified was too low for the families to accept, in subsequent negotiations with the victims and families USIA agreed to pay damages that amounted to a total of $628,000—a figure equivalent to more than $9 million today.

An Industry’s Contraction and Prohibition’s Rise

The Great Molasses Flood was more than an industrial disaster—it was a harbinger of the upheaval that Prohibition would soon unleash. The holding tank’s collapse exposed the reckless urgency with which USIA raced to stockpile reserves before the Volstead Act slammed the doors on legal production. Within a year of the disaster, USIA had shuttered its Boston operations—long before the remnants of the sticky substance disappeared from the North End. But while the company could flee the scene of the crime, thanks to the dogged pursuit of justice by Ogden and his team, the company could not escape the consequences of its negligence.

Prohibition itself brought further chaos to USIA and the rest of the distilling industry. Almost overnight, the legal market for alcohol dried up, plunging ethanol distillers into more than a decade of financial instability.

Black markets flourished and scofflaws seized the moment, ushering in an era where rules broke faster than speed boats racing back to Cape Cod from Rum Row.

But we will save those exciting details for another stop on the New England Prohibition Road Trip.

From the New York Times, May 11, 1924.

Where the Tank Once Stood

While completing my doctorate at Harvard, I lived in the North End, just a block from where the molasses tank stood. Decades after the explosion, I would pass brick walls still streaked with the remnants of that day—thick, angry tear-shaped stains 12 feet above the street. And yes, on hot July nights, I fancied a sweet scent wafted through the open window of my fourth-floor apartment.

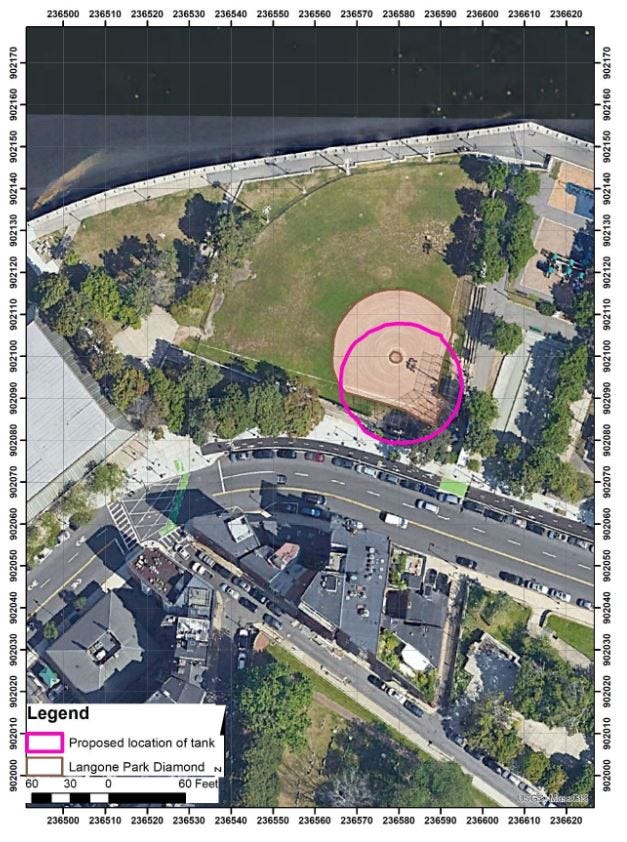

A few years ago, researchers from UMass Boston tracked down the actual site of the ill-fated tank, a stone’s throw from the pitcher’s mound in what is now Langone Park. There is also a plaque embedded on a wall at the park’s entrance, commemorating the flood—an understated reminder of the disaster.

Photo courtesy of the Fiske Center at UMass Boston.

There is a certain poetic justice to how this space has evolved. Langone Park now serves as a bustling gathering place for the community—where life and laughter have come to drown out the sad echoes of a somber past. Fittingly, it bears the name of Joseph Langone, Jr., the son of an Italian immigrant. And while the ground may no longer be sticky with molasses, the memory of what happened there clings to the neighborhood, seeping into the new stories its residents tell.

Places In And Around The North End Associated with the Great Molasses Flood

Nothing beats standing on the ground where history itself poured out, at Langone Park (529 Commercial Street, Boston). In the summertime, you can catch a baseball game or take in the view from the benches on Copp’s Hill terrace (520 Commercial Street, climb the stairs for the best view). In the winter, lace up your ice skates at Steriti Memorial Rink (571 Commercial Street, Boston). You can see where the molasses tank stood through the rink’s oversized windows.

Since the North End has become known for its Italian heritage and traditions, visitors are honor bound to consume at least one good Italian pastry. With the closing of Maria’s Pastry Shop a few years back, the best option is now Modern Pastry Shop (257 Hanover Street). Let the tourists go to Mike’s.

If you’re interested in a first-hand telling of the investigation of the Great Molasses Flood, the Social Law Library (1 Pemberton Square, #4100, Boston, MA) opposite Boston City Hall has one of the few existing reports from Hugh W. Ogden, summarizing the testimony leading to the decision that laid the fault for the catastrophe at the feet of USIA. Members of the public can get a day pass and read the non-circulating document on site.

If you want to keep walking, there are some fine examples of Art Deco buildings in downtown Boston, A self-guided tour can be found here: Boston Art Deco: A Virtual Tour,

If you’d like to venture a little further, a short ride on the Red Line (the metro) will take you to Arthur Jell’s former residence near Harvard Square. The apartment building where he lived for more than a decade still stands at 84 Prescott Street (Cambridge), a block from Harvard Yard.

And no Prohibition Road Trip is complete without a stop at a bar, so on your way back from Arthur Jell’s place, check out the Carrie Nation Cocktail Club (11 Beacon Street, Boston). The bar opened in 2013 and has the feel of a speakeasy.

If you’d prefer to experience the real thing, you can head out to the South End and J.J. Foley’s Café (117 East Berkeley Street, Boston), which opened in 1909.

Sources and Further Reading

Andrews, E. (2023). The Great Molasses Flood of 1919. https://www.history.com/news/the-great-molasses-flood-of-1919

Kole, W.J. (2016). Slow as molasses? Sweet but deadly 1919 disaster explained. https://phys.org/news/2016-11-molasses-sweet-deadly-disaster.html)

McCann, E. (2016). Solving a mystery behind the deadly ‘tsunami of molasses’ of 1919. Solving a Mystery Behind the Deadly ‘Tsunami of Molasses’ of 1919 - The New York Times

Ogden, H.W (c. 1928). Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Superior Court, Suffolk ss, no. …:… v. United States Industrial Alcohol Company or U.S. Industrial Alcohol Company: Auditor’s report. Non-circulating report available at the Social Law Library, Boston, MA.

Puleo, D. (2003). Dark tide: The Great Molasses Flood of 1919.

Steinberg, J.M. & G.E. Bello (2019). Results of geophysical survey at Langone Park: 100 years since the Great Molasses Flood. Results of Geophysical survey at Langone Park: 100 Years since the Great Molasses Flood

Information about Arthur Jell’s immigration to the US, residence in Massachusetts and New Jersey, and other vital records can be found at FamilySearch.org.

For Arthur Jell’s residence in Cambridge, MA, the information came from the following source: United States Census, 1910, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M2VW-KQD : Sun Jul 07 21:42:40 UTC 2024), Entry for Arthur P Jell and Gwendlyn A Burton, 1910.

Information about Arthur Jell’s birth and service in the Essex Fusiliers can be found in the Government of Canada’s archives. Collection search

Photographs are courtesy of the Boston Public Library’s Flickr collection. Molasses Disaster, Boston, Mass., 1919 | Flickr